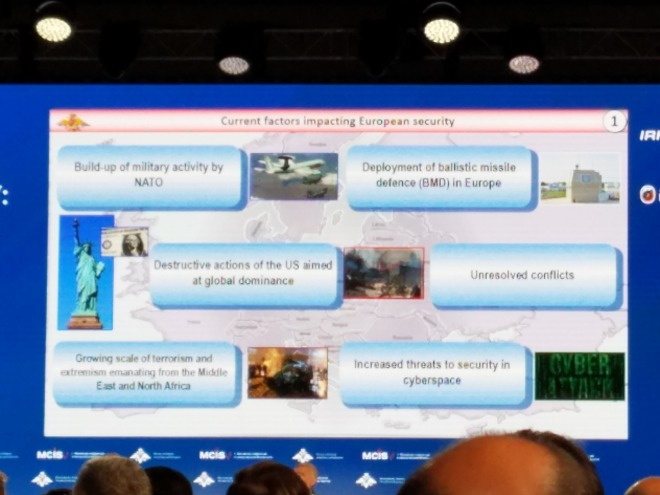

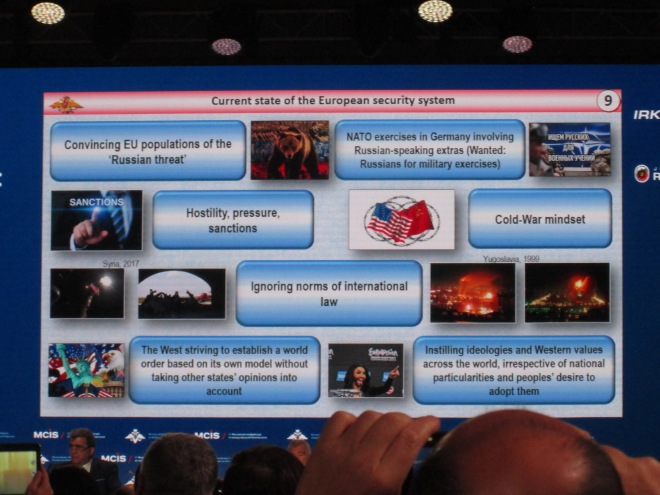

Here’s the second installment of my reporting from the 2015 MCIS conference. This one and the next will focus on Russian views of NATO as the primary source of military threat to the Russian Federation. The first speech was by General Valery Gerasimov, the Chief of the General Staff. His topic was the military threats and dangers facing Russia in the contemporary period. He launched into a discussion of how the West saw Russia’s efforts to stabilize the situation in Ukraine as unacceptable independence in standing up for its national interests. He argued that this reaction was the cause of the increase in international tension over the last year, as the Western countries have sought to put political and economic pressure on Russia in order to “put it in its place.” He argues that while many Western experts believe that the Ukraine crisis has led to a sudden and rapid collapse of world order, the reality is that the situation has been developing since the start of the 1990s. The problems were caused by the collapse of the bipolar system, which allowed the US to consider itself the winner of the Cold War and to attempt to build a system in which it had total domination over international security. In such a system, the US would decide unilaterally which countries could be considered democratic and which were “evil empires,” which were freedom fighters and which terrorists and separatists. In doing so, the US stopped considering the interests of other states and would only selectively follow the norms of international law.

Russia has had to respond to this threat and has done so in its new military doctrine, which strictly follows international norms. The key points, as presented by Gerasimov in the slide below, include using violent means only as a last resort, using military force to contain and prevent conflicts, and preventing all (but especially nuclear) military conflicts. At the same time, the doctrine states that the current international security system does not provide for all countries to have security in equal measure. In other words, Russian military leaders continue to feel that Russian security is infringed by the current international security system and imply that they would like to see it revised.

The most significant threat facing Russia, in Gerasimov’s view, comes from NATO. In particular, he highlights the threat from NATO enlargement to the east, noting that all 12 new members added since 1999 were formerly either members of the Warsaw Pact or Soviet republics. This process is continuing, with the potential future inclusion of former Yugoslav republics and continuing talk of perspective Euroatlantic integration of Ukraine and Georgia. Political arguments about creating a single Europe sharing common values have outweighed purely military and security in enlargement discussions, with many new members added even though they did not fulfill the economic and military criteria for membership. This expansion has had a serious negative effect on Russia’s military security.

In addition to NATO enlargement, NATO has also expanded cooperation with non-member countries in the region through programs such as the Partnership Interoperability Initiative, which includes Georgia, Moldova and Ukraine among 24 priority countries for cooperation, and Privileged Partnership, which will allow NATO to use infrastructure in Finland and Sweden to transfer troops to northern Europe. Furthermore, NATO is actively seeking to increase its influence in Central Asia and the Caucasus.

NATO is using the crisis in Ukraine as an excuse to strengthen the forces it has arrayed against Russia. It has openly blamed Russia for aggressive policies in the post-Soviet space and has made containment of Russia the prime force for future development of NATO. The decisions made at the Wales NATO summit in September 2014 confirm this.

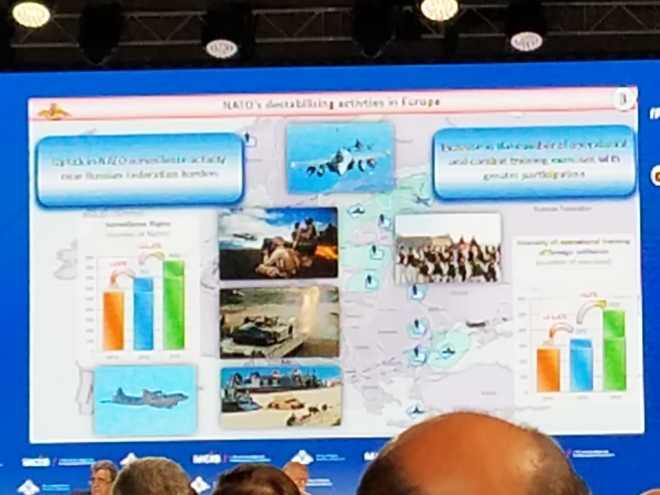

While NATO military activity near Russia was relatively stable through 2013, it has increased substantially over the last year. NATO states’ naval presence in the Black Sea has quadrupled, flights by reconnaissance and tactical aviation have doubled, and flights by long range early warning aircraft have increased by a factor of nine. US UAVs are flying over the Black Sea, while German and Polish intelligence ships are constantly present in the Baltic. The number of NATO exercises increased by 80% in 2014 compared to the previous year. The character of these exercises has also changed. Whereas in the past they were focused primarily on crisis response and counter-terrorism, now they are clearly aimed at practicing military action against Russia.

The action plan approved in Wales included a significant increase in NATO military presence in Eastern Europe and the Baltics, including a rapid reaction force and a constant presence of a limited contingent of forces rotating through the region. This will allow a large number of NATO military personnel to be trained to conduct operations against Russia. At the same time, military infrastructure, including weapons storage facilities, is being built up in Eastern Europe. Gerasimov argued that on the basis of all of these developments, it is clear that efforts to strengthen NATO’s military capabilities are not primarily defensive in nature.

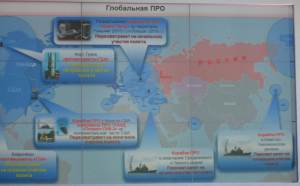

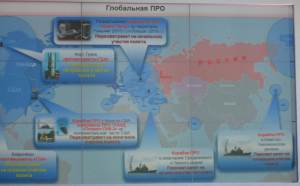

Gerasimov then turned to the question of US efforts to develop global ballistic missile defense systems. He argued that Russia views the development of these systems as yet another move by the US and its allies to dismantle the existing international security system on their way to world domination. Over the last four years, US BMD systems have begun to appear near Russian borders, including Aegis-equipped ships in the Mediterranean and Black Seas, Aegis Ashore systems in Romania and Poland, and anti-missile systems being deployed in the Asia-Pacific region with Japanese and South Korean cooperation.

These forces present a real threat to Russian strategic nuclear forces and could also strike Russian satellite systems. Washington has so far refused to share command authority for global BMD systems, even with its allies, making it clear that it alone will decide which NATO member states it will defend from missile threats. Since Russia will have no choice but to take counter-measures against global BMD systems, this may subject non-nuclear NATO-member states to the risk of being early targets of Russian response measures.

What’s more, the deployment of anti-missile systems violates the INF treaty, since the Aegis Ashore systems can be armed with Tomahawk cruise missiles as easily as with SM-3 anti-missile systems.

Russia is also concerned with the development of the concept of Prompt Global Strike, which will also damage the strategic nuclear balance that currently provides the main guarantee for international stability.

In its efforts to “put Russia on its knees,” Washington and its NATO partners continue to create crises in territories on Russia’s borders. Having successfully carried out regime change scenarios under the guise of colored revolutions in Ukraine, Georgia, and Moldova, the US was able to place anti-Russian governments in power in a number of states bordering Russia. The radicals and Russophobes who came to power in Ukraine in 2014 have based their policies on blaming Russia for all of Ukraine’s problems while persecuting the country’s Russophone population. They are now trying to use force to repress their own citizens who expressed a lack of confidence in this new government. As a result, Ukraine has been plunged into civil war. Gerasimov said that it is difficult to know how the conflict will end, since “we don’t know what directives Ukrainian leaders will receive from their Western ‘curators’ and where Kiev’s aggression may be directed in the future.” But it is clear that these actions pose a military threat to Russia, much as the Georgian attacks on Russian peacekeepers in South Ossetia in 2008 did. Gerasimov also noted that Mikheil Saakashvili, who ordered these attacks, is now an advisor to Ukrainian President Poroshenko.

Gerasimov then moved on to a discussion of other frozen conflicts in the post-Soviet space, noting the increased risk that these conflicts may be “unfrozen” as a result of the currently heightened threat environment. He noted statements by the current Georgian government reflecting its intention to restore control of Abkhazia and South Ossetia by force. The Moldovan government has been pressing for the withdrawal of Russian peacekeepers from Transnistria while continuing its economic blockade of the region. This is all leading to an increase in tension in these regions and may result in response measures from the Russian side.

In conclusion, Gerasimov turned to the threat posed by global terrorism. He noted that the number of members of various extremist organizations has grown from 2000 in the 1960s-70s, to 50,000 in the 1990s, to over 150,000 today. He also expressed concern about the growth of transnational terrorist networks, including some such as ISIS that have developed certain aspects of statehood. Some ISIS fighters are Russian citizens. These fighters threaten the entire world and attempts to fight the threat by a US-led airstrike operation have so far not achieved visible results. As a result, Washington and Brussels have once again turned to developing new armed groups among so-called “moderate Islamists.” But such projects do not take into account how such terrorist empires have formed in the past. Al-Qaeda, for example, formed from mujahideen who were funded by the US and its allies. Similarly, ISIS fighters until recently were “good” fighters but have now gone out of Western control and started to threaten their former sponsors.

In response to this range of threats, Russia has continued to develop its armed forces. Nuclear forces are maintained at a level designed to guarantee nuclear deterrence, including modern systems that can overcome US BMD systems. Russian Air-space defense systems continue to be developed. Defensive forces have been placed in Crimea. Russian bases have been placed in Abkhazia, South Ossetia, Armenia, Kyrgyzstan, and Tajikistan. These bases will serve as a guarantee of stability and security in these regions.

At the same time, Gerasimov noted that Russia understands that most modern security threats affect entire regions and even the whole world so that their solution requires international dialog and cooperation.

—-

I’ll have some reactions to this speech in a follow-up post. For now, let me just say that it was interesting to see the shift to the discussion of “old school” military threats, following last year’s focus on colored revolutions and hybrid warfare.