I’m going to be participating in the following panel tomorrow. Great lineup, encourage those interested to sign up.

The November 25 naval skirmish between Russian and Ukrainian forces in the Kerch Strait was significant first and foremost as an open military confrontation between the two countries’ armed forces. But it also highlighted the fraught legal status of the strait and the Azov Sea, a status that Russia has been exploiting in recent months to exert political and economic pressure on Ukraine.

The confrontation began months before the recent events that brought the conflict to worldwide attention. In March 2018, Ukrainian border guard vessels detained a Russian fishing vessel in the Azov Sea for violating exit procedures from the “temporarily occupied territory of Ukraine”, namely from Crimea. The crew of that vessel remained in detention for several months, until they were exchanged in October for Ukrainian sailors. The captain of the Russian ship remains in Ukraine and is facing prosecution for illegal fishing and “violation of the procedure for entry and exit from the temporarily occupied territory of Ukraine”. Since that incident, Russia has retaliated by detaining several Ukrainian fishing vessels.

In May, Russia also began to regularly hold Ukrainian commercial ships for inspection before allowing them to pass through the Kerch Strait. The initiation of this inspection regime largely coincided with the opening of a road and rail bridge across the strait. Russia claimed that the inspections were required to ensure the safety and security of the bridge at a time when some Ukrainians had publicly threatened to attack the bridge. The delays caused by the inspection regime, together with ship height restrictions caused by the bridge, have led to a 30 percent reduction in revenues at Ukraine’s commercial ports of Mariupol and Berdyansk, raising fears that Russia is trying to strangle the economy of eastern Ukraine.

In the same period, Russia also began to build up its naval presence in the Azov Sea, with at least three missile ships based there since summer 2018. Reports indicate that Russia plans to set up a full-fledged flotilla in the Azov in the near future. Ukraine has also strengthened its naval presence in the region, placing several armoured boats in Berdyansk and seeking to expand the base there.

The transfer of ships from Odesa to Berdyansk that caused the skirmish was part of this effort. Ukraine had moved naval ships through the Kerch Strait as recently as September 2018, but these ships were not armed. In that case, the ships were allowed to pass through without incident, although they were closely followed by Russian border guard vessels. The passage of two armoured boats through the strait in late November was thus the first attempt by the Ukrainian Navy to bring armed ships through the Kerch Strait since tensions began to mount and the bridge was completed in spring 2018.

The status of the Azov Sea and the Kerch Strait is regulated by a bilateral treaty that was signed by Russia and Ukraine in 2003. According to the terms of the treaty, the sea is considered to be internal waters for both countries, and both Ukrainian and Russian commercial and military ships have the right of free passage through the strait. Furthermore, the treaty does not specify any particular advance notice procedures for passage through the strait. Foreign commercial ships are allowed to pass through the strait and enter the sea if they are heading to or from a Ukrainian or Russian port. Military ships belonging to other countries may be allowed passage if they are invited by one of the signatories to the treaty, but only with the agreement of the other signatory. In 2015, Russia unilaterally adopted a set of rules requiring ships passing through the strait to give advance notification to the Russian authorities, ostensibly to assure safety of navigation. These rules have not been accepted by Ukraine.

Michael Kofman and I published a short analysis of the naval battle in the Kerch Strait on the Monkey Cage. Here’s a sampler.

The Nov. 25 skirmish between Russian Border Guard and Ukrainian navy ships in the Kerch Strait has escalated tensions not just between the two countries, but also between Russia and NATO.

Two Ukrainian navy small-armored boats and a tugboat attempted to cross into the Sea of Azov via the Kerch Strait. A Russian Border Guard ship rammed the tug. Russian forces eventually captured all three boats, holding them in the Crimean port of Kerch.

This crisis kicked off months ago

In March 2018 Ukraine seized a Russian-flagged fishing vessel, claiming that it had violated exit procedures from the “temporarily occupied territory of Ukraine.” Although the Russian crew was released, the boat remains detained in a Ukrainian port. Subsequently, Russia began to seize Ukrainian vessels for inspection, starting in May when a fishing vessel was detained for illegally fishing in Russia’s exclusive economic zone.

A new Russian-built bridge linking Crimea to southern Russia is at the center of Russia’s attempt to assert sovereignty over the entire Kerch Strait. The bridge opened in May, and its low clearance height cut off many commercial ships and reduced revenue at the Mariupol port by 30 percent. Russia has imposed an informal blockade on the remaining maritime traffic, with ships often waiting more than 50 hours to cross, and Russian authorities insisting upon inspecting the cargo. This has substantially raised transit costs — and has been slowly strangling the Ukrainian ports of Mariupol and Berdyansk.

To read the rest, please click here.

After a bit of a break, I’m resuming posting my briefs for Oxford Analytica, as always with a three month lag. This was written in early September, just after the conclusion of the ceasefire. (Note that this version is not identical to that published by Oxford Analytica, as I have removed some material that was added by the editorial staff.)

—–

SIGNIFICANCE: At the start of the conflict in Donbas, the Ukrainian military appeared to be almost completely incapable of defending its territory. Kiev’s forces were unprepared for Russia’s annexation of Crimea and seemed powerless to prevent it. In recent months, it has become a somewhat more effective war-fighting force, though not one that is powerful enough to withstand a full-scale future Russian military invasion. If the current ceasefire fails and Russia intervenes fully in Donbas, the Ukrainian military will not have the capability to defend the country.

Impact

ANALYSIS:

At the start of the conflict, Ukraine’s military appeared on paper to be a fairly sizeable force, with almost 130,000 active military personnel, over 1,000 tanks, 370 combat aircraft and helicopters, and almost 2,000 artillery pieces. At the same time, it was notoriously underfunded and in disarray as a result of a recent political decision to end conscription and shift to a fully professional manning model. The total number of usable troops and equipment in the ground forces amounted to 80,000 personnel, 775 tanks, 51 helicopters, fewer than 1,000 artillery pieces and 2,280 armoured personnel carriers.

Military dispositions

These troops were positioned in a manner that showed the Ukrainian military’s history as a legacy Soviet force, with the vast majority of units stationed in western Ukraine and along the southern coast. No units were located in the Luhansk or Donetsk regions. Only a single mechanised brigade was located in neighbouring Kharkiv region, while the largest concentration of Ukrainian troops in eastern Ukraine was based in the Dnipropetrovsk region.

Yanukovich’s neglect of military

Some reports indicated that the size of the combat-ready force was even smaller, with only 6,000 troops fully prepared to fight when the conflict broke out. Other units were not considered combat-ready because of a combination of lack of training and inadequate and poorly maintained equipment.

The Ukrainian military received limited funding throughout the post-Soviet period. This tendency became even more pronounced during Viktor Yanukovich’s presidency. He was more concerned about internal unrest than external threats and therefore increasingly shifted the country’s limited security budget towards internal security forces at the expense of the regular armed forces. As a result, the military budget remained very low, at just over 1% of GDP, throughout Yanukovich’s presidency.

Political chaos hampered military response

In addition to underfunding, Ukrainian forces were initially unprepared to deal with the crisis because of a combination of political chaos and internal subversion. The initial Russian intervention in Crimea took place immediately after the chaotic final stage of the ‘Maidan’ revolution. The newly formed acting Ukrainian government had not yet established its authority in Kiev, much less in the eastern and southern regions that had largely opposed Maidan. It was not prepared to act in response to Russia’s immediate and fast-paced operation in Crimea.

Russian infiltration

Widespread infiltration of the Ukrainian government, military and security services by Russian agents also contributed to disorganisation and poor performance. It appears that these agents were able to provide Moscow with detailed information on Ukrainian government and military planning for responding to the conflict. Highly placed military officers whose sympathies were with Russia and the east Ukrainian separatists may also have played a role in disrupting military planning. At the local level, unit commanders who sympathized with the separatist cause withdrew their personnel and turned their equipment over to the insurgents on several occasions. These surrenders provided the means for separatist forces to receive their first parties of heavy weapons and armored vehicles.

Lack of counter-insurgency training

The Ukrainian military was trained to respond to an invasion and to participate in peacekeeping operations abroad. It had neither plans nor training to fight an insurgency.

For all of these reasons, Ukraine’s military and security forces were unprepared to counter either the Russian military occupation of Crimea or the subsequent emergence of armed separatist forces in eastern Ukraine.

Partial resurgence

The Ukrainian military used a unilateral ceasefire in late June to rebuild its command structure, develop new tactics and recruit personnel. Most of the senior military leadership was replaced, with incompetent and compromised generals being forced out in favour of those who had shown the most initiative and/or were seen as loyal to Kiev.

Around this time, the government decided to use military tactics against the separatists. This led to an escalation of the conflict and an increase in civilian casualties, but also allowed it to use regular military units against separatists.

Irregular battalions

Kiev determined that it did not have enough regular military personnel to counter the insurgency in Donbas while simultaneously maintaining a standing force to face potential Russian aggression from Crimea. Kiev began to organise irregular militia battalions. A number of territorial defence battalions, special purpose police battalions, national guard battalions and other independent units have been formed through the recruitment of volunteers. These include several units that have gained some notoriety in the fighting, such as the Azov and Donbas battalions, as well as independent units associated with the Right Sector and the Organisation of Ukrainian Nationalists.

Oligarch armies

Some of these battalions are sponsored by wealthy Ukrainians such as Igor Kolomoisky, the governor of Dnipropetrovsk region, who allegedly spent millions of dollars organising and arming fighters from Dnipropetrovsk.

Ideological and political battalions

Some of the new battalions are organised around nationalist ideology such as the Azov battalion, while others comprise people who participated in the Maidan protests (the Maidan and Aidar battalions). Additionally, there are some tied to political parties (the Batkivshchyna and Right Sector battalions).

However, the vast majority of the battalions were initially organised as territorial defence units and were only later sent to fight in eastern Ukraine. As of late June, the total approximate strength of these battalions was estimated at 5,600, with the Donbas Battalion the single largest with almost 1,000 fighters. Several of the units suffered major losses in battles in July and August, although in some cases they have also been able to recruit reinforcements.

Popular support for war effort

The parlous state of Ukrainian government finances and the reluctance of Western governments to provide financial and military assistance have necessitated efforts to raise money and provide basic supplies for government forces and especially for irregular pro-government fighters through donations from the Ukrainian population and from the diaspora abroad. To this end, a number of websites and social media resources have been organised to raise money for fighting the conflict.

These efforts have been primarily useful in providing basic supplies for military units, especially the irregular battalions. Such supplies, detailed in frequent reports on assistance websites, consist primarily of medicines, spare parts and maintenance, rather than the purchase of weapons or major equipment. They are not a replacement for regular procurement and recruitment, but have played a role in spurring the government to speed up resupply and increase the financing of regular military units.

Ukrainian internet crowdsourcing efforts have expanded beyond financial assistance. The website Stop Terror in Ukraine has used crowdsourcing to report separatist attacks, troop movements, roadblocks and the seizure of buildings throughout the country. The effectiveness of such efforts remains unclear but they do show that the war effort has widespread popular support.

Military unable to withstand increased Russian assistance

As a result of the improvements in capabilities described above, Ukrainian forces scored substantial victories against the separatists throughout July and in early August. By August 15, separatist forces had lost more than half of the territory they controlled prior to the ceasefire, were divided into several enclaves and had come close to losing the ability to transfer forces among strongholds. Ukrainian military and political leaders believed that they could defeat the separatists and retake all of the territory in eastern Ukraine not under government control within a few weeks.

However, their continued success depended on static levels of Russian assistance to the separatists. The Ukrainian leadership gambled that Russia would not seek to escalate its involvement in the conflict. However, Russia proved them wrong, first by providing greater levels of heavy weapons and volunteer fighters to separatist forces, then by shelling Ukrainian forces from Russian territory in order to prevent the latter from blocking separatists’ access to Russian assistance via the common border and finally by opening a new front in territory previously under the firm control of government forces — around Novoazovsk and Mariupol.

“Ceasefire in name only”

This escalation in Russian military assistance has in recent weeks caused a major shift in the path of the conflict, with Ukrainian forces taking heavy casualties throughout Donbas and losing control of approximately half of the territory they had gained over the summer. The current ceasefire is holding — although Supreme Allied Commander Europe General Philip Breedlove of the US Air Force commented in Vilnius recently that the ceasefire was a “cease-fire in name only” — and a return to serious fighting is a distinct possibility. Russian support for the Donbas separatists will remain.

Prospects for Ukrainian forces

As shown by recent events, despite modest improvements in capabilities since the spring, Ukrainian forces are not currently capable to withstand attacks by even small numbers of well-trained regular Russian forces for any length of time. In part, this is the result of the disparity in training received by Ukrainian forces compared to elite Russian forces.

Yet the greater role in Ukrainian forces’ weakness comes from the disparity in equipment. The use of powerful air defence weapons provided by Russia largely negated Ukraine’s air superiority throughout the summer.

CONCLUSION: The Russian government has made clear that it will take steps to ensure that the Ukrainian military does not defeat separatist forces in eastern Ukraine. It will use as much force as it deems necessary to ensure that the separatist enclaves in Donbas remain functional. There is no way for the Ukrainian government to end the conflict through a military victory. Should the ceasefire fail and Ukrainian forces overcome their setbacks and renew their advance into separatist territory, Moscow is likely further to escalate the extent of its direct military assistance.

Moscow’s Center for Analysis of Strategies and Technologies has just published a new book on the military aspects of the Ukraine crisis. Here’s a preview of my book review, published today at War on the Rocks.

Colby Howard and Ruslan Pukhov, eds. Brothers Armed: Military Aspects of the Crisis in Ukraine (East View Press, 2014).

Over the last few months, the crisis in Ukraine has led to a fundamental reassessment of the state of U.S.-Russia relations. The crisis began with Russia’s almost completely non-violent military takeover of Crimea in February-March 2014. A new English-language volume edited by Colby Howard and Ruslan Pukhov highlights the causes and nature of the conflict in Crimea, as well as provides some lessons for both Ukraine and other states that might be subject to Russian aggression in the future.

This volume provides balanced and comprehensive coverage of virtually all military aspects of the conflict in Crimea, including both Russian and Ukrainian points of view. The experts from the Center for Analysis of Strategies and Technologies (CAST) are some of the top Russian military analysts and the quality of their research and understanding of the Russian and Ukrainian militaries is clear in the writing.

The book begins with a short chapter by Vasily Kashin describing the backstory of the territorial dispute over Crimea. Although it starts with the conquest of the region by Catherine the Great back in the 18th century and mentions more familiar arguments related to the legitimacy of the region’s transfer from Russia to Ukraine in 1954, the main focus is on events after the break-up of the Soviet Union. Kashin highlights tensions over Crimea’s status within Ukraine throughout the 1990s, the role played by former Moscow mayor Yuri Luzhkov in promoting pro-Russian separatism in Crimea in the 1990s and 2000s, and the contentious negotiations over the division and subsequent status of the Black Sea Fleet and its base in Sevastopol. His key insight is that “the Russian government took no serious measures to support separatist movements in Crimea” prior to its invasion of the peninsula last February. This illustrates that Russian actions during the crisis were not the culmination of a plan to dismember Ukraine, but a reaction to the perceived security threat coming from the Maidan protests that culminated in the overthrow of the Yanukovych government.

To read the rest, please click here.

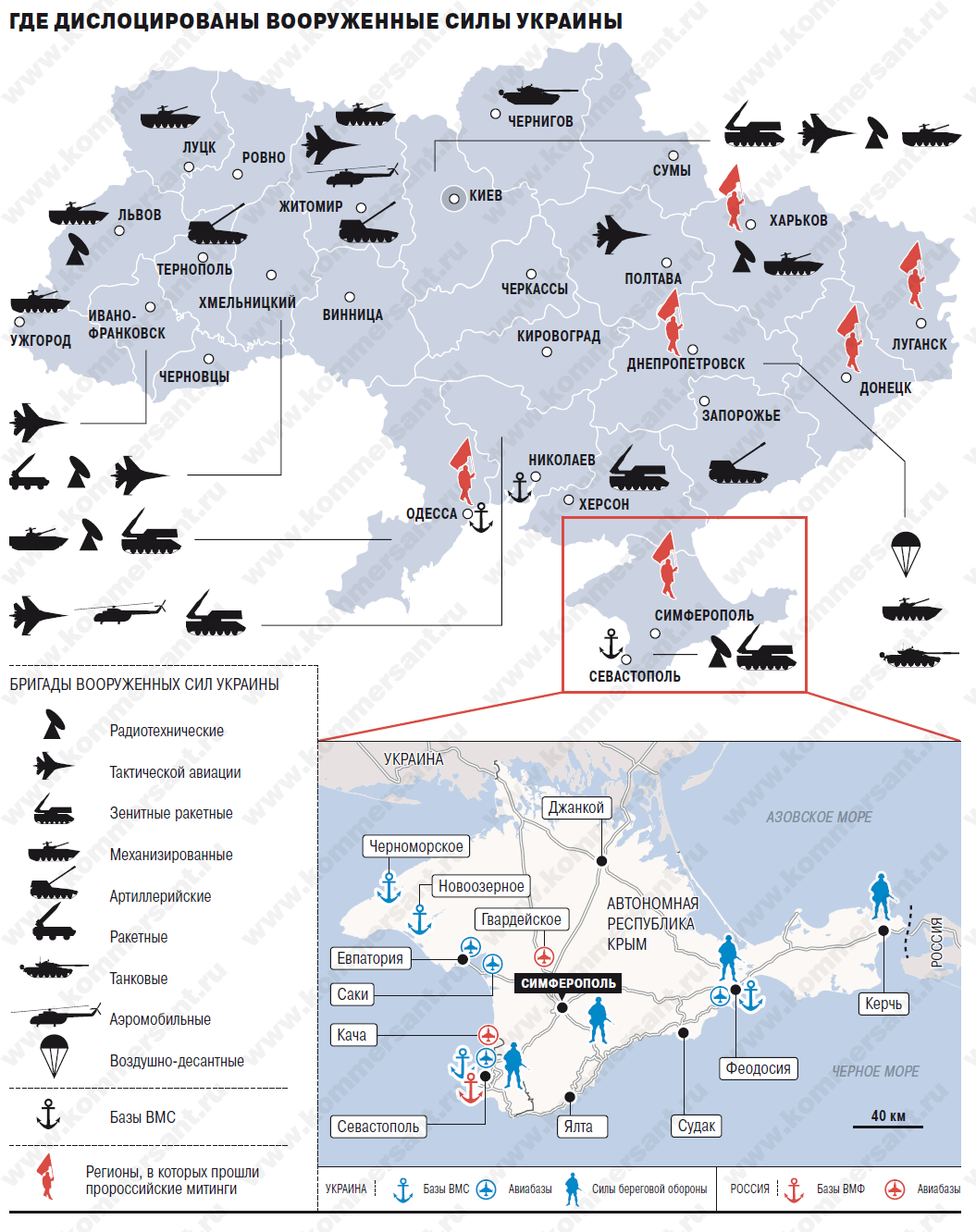

Here’s a useful map of the locations of Ukrainian military bases (as of 2008) and Russian forces located near Ukraine’s borders. It’s drawn from a new Russian language blog, and due to limited time I haven’t checked the accuracy of the map, I’m afraid. Feel free to note any inaccuracies in the comments.

Note that the majority of Ukraine’s forces are located in Western Ukraine, as the positioning of the forces is left over from the Soviet period, when they were placed so as to maximize Soviet defensive potential against NATO forces. There are two mechanized infantry brigades, a tank brigade, and an artillery brigade in the east, though, as well as airborne brigade and a tactical aviation brigade. Compare this to western Ukraine, where there are five mechanized infantry brigades, two artillery brigades, a tank brigade, a rocket brigade, four tactical aviation brigades, two army aviation regiments, and an air mobile brigade. Also worth highlighting the forces located in the south, near the Crimea: one mechanized infantry brigade, a tactical aviation brigade, an air mobile brigade and an army aviation regiment.

Here’s another map from the same source, with just the Ukrainian forces shown.

The accompanying text notes that the total personnel of Ukraine’s armed forces consists of 184,000 people, including 93,000 in ground forces. These are comprised of four tank brigades, 15 mechanized infantry brigades, 15 artillery brigades, two rocket brigades, 3 air mobile brigades, one airborne brigade, and one air mobile regiment. (Obviously this doesn’t match the numbers on the map) The air force has 160 combat and 25 transport aircraft. Of course, it’s likely that only a relatively small percentage of these units are combat-ready, especially in the air force.

I was on the Foreign Entanglements video blog yesterday with Robert Farley, talking about Ukraine. Here is the show description with links to the various segments, or you can just watch the whole thing.

On Foreign Entanglements, Rob and Dmitry discuss the recent Russian incursion into Crimea. Dmitry summarizes Russian interests in the region. Have the US and Europe handled the situation correctly so far? Dmitry suggests that, in the long run, Putin will pay substantial costs for the incursion. Is the new Ukrainian government stable enough to fight back? Rob and Dmitry compare the strengths of the Russian and Ukrainian militaries. Finally, Dmitry thinks through some options for the Western response.

I’ve avoided writing anything on the situation in Ukraine, because there’s so much material being written already and I’m not an expert on the Ukrainian military. But I do want to make just a couple of quick points.

1) Russian military experts seem to have been caught up in their government’s propaganda. This is especially disappointing when it comes from usually top-notch analysts such as Ruslan Pukhov and Igor Korotchenko. In an article that was picked up and translated by Russia Beyond the Headlines, they display a frightening amount of self-delusion in arguing that Ukrainian troops are not combat-capable simply because they stayed in their barracks while Yanukovych was being deposed. To assume, as Korotchenko does, that a military that stays on the sidelines during an internal conflict will not be able to act in the event of a Russian invasion betrays a willful lack of understanding of the difference in motivation between intervening in an internal conflict and defending your country when it’s under attack. Pukhov argues that because the army is made up of contract soldiers, local Crimean boys will not fight the Russians. This is a much more serious possibility and may well turn out to be the case, but so far there are at least a number of units that are refusing to submit to the “polite people” without insignia that are surrounding their bases. For the moment (and thankfully), they have not received any orders to fight, so the jury is still out on this question.

Now from what I know, the Ukrainian military is not in particularly good condition and would undoubtedly lose to the Russian military in any serious conflict. But that doesn’t mean that it would not be able to inflict some serious pain on its opponents in the process. And I would venture that should the conflict spread to “mainland” Ukraine, the soldiers would be highly motivated to defend their homeland.

2) Some Western analysts have argued in recent days that Putin is scoring a massive victory by taking Crimea with pretty much no resistance. But it seems to me that this action was taken not as a triumphant victory but as an effort to avoid what Putin perceived to be a complete geopolitical rout in the aftermath of the defeat of Yanukovych. This seems quite short-sighted to me, as without the Russian intervention the Maidan forces were likely to fall to squabbling and would have most likely come to a relatively quick accommodation with Moscow. Now, it appears that the likeliest scenario is that Putin gets Crimea as a client state (or new province to subsidize) while permanently losing any influence in the rest of Ukraine. The majority of Ukrainians in eastern and southern Ukraine have no desire to be ruled by Putin and will support their leadership while the threat of Russian invasion persists, absent any really stupid polarizing actions on the part of said leadership. I would count this as a net strategic loss for Putin.

The second likeliest scenario is a Russian intervention in eastern Ukraine, leading to a quite bloody and potentially long-lasting conflict with Russian troops involved. Even though Russia would be likely to win such a war, the result would be long term instability on Russia’s immediate border, with guerrilla warfare likely for some time. And Russia would have to bear the full cost of supporting Ukraine for the foreseeable future. This would be an even bigger strategic loss for Putin.

Putin has also already lost all of the international goodwill generated by his investment in the Sochi Olympics. He is gambling that EU states will fail to impose any serious penalties on Russia for its actions. Given past history this may seem to be a reasonable bet, but sending Russian troops into Ukraine is likely to be seen as a game-changer in the most important European capitals, including Berlin, London, Paris and Warsaw. While sanctions are by no means guaranteed (especially if Russian intervention remains limited to Crimea), they are more likely than one might expect given Europe’s general unwillingness to act.

For more on this, I would suggest that readers take a look at Mark Galeotti’s assessment, which parallels mine in many ways.

Much has been written in the last few days on the political and economic implications of the agreement signed by Ukraine and Russia to extend the Sevastopol naval base lease through 2042. Important as they are, I won’t reprise those arguments here. Instead, I would like to briefly discuss the consequences of the agreement for the future of the Russian military.

As I have written before, the Black Sea Fleet is essentially a dying enterprise. One recent Russian report argues that 80 percent of its ships will need to be written off in the near term. Its current order of battle consists of 37 ships. The missile cruiser Moscow (currently on an extended deployment) is the flagship. There is also one other cruiser, one destroyer, two frigates, 13 corvettes and missile boats, and 3 patrol craft. There are also 7 littoral warfare ships, 9 minesweepers, and 1 diesel sub. The average age of these ships is 28, which makes it the oldest fleet in the Russian Navy. The Alrosa submarine recently suffered an engine fire and almost sank. It is likely to be under repair for the foreseeable future. The Kerch cruiser was recently overhauled, but is old enough that it is likely to be retired in the near future anyway. All reports indicate that it cannot go out into the open sea. The other ships will last a bit longer, but by and large just about all the current combat ships of the Black Sea Fleet (with the exception of two relatively new minesweepers) will need to be retired within 10-15 years.

Along with the lease extension, several Russian officials and experts have stated that the Black Sea Fleet will now receive a number of new ships, including the first two Gorshkov-class frigates, currently under construction in St. Petersburg, two new corvettes (presumably Steregushchiy-class), and 2-3 diesel submarines. The likelihood of the fleet receiving all of these ships in the near term is close to zero. First of all, completion of the Admiral Gorshkov has been repeatedly postp0ned. A recent report indicates that it is still only 28% completed, despite having been under construction for four years already and having an expected commissioning date of 2011. The second ship’s keel was laid in 2009. Even if construction speeds up, it seems to me that the BSF will not get either ship before 2013 at the absolute earliest, with 2015 a more likely target. The Steregushchiy class of corvettes seems to be more successful, and given the expected completion dates of ships currently under construction, the BSF could well get two of those within the next two years. As for the submarines, the first sub of the Lada class has had a lot of problems during sea trials. It was finally delivered to the Navy last weekend, six years after it was launched and 13 years after construction began. Construction of the first Lada that is destined for the BSF began in 2006. Even if the process is far smoother than with the St. Petersburg, I would expect it to enter the fleet no earlier than in 2013.

Finally, there’s the speculation about the Mistral. I have previously argued that Russia would be unlikely to place a Mistral ship in the Black Sea Fleet. I still think that’s the case, though if it purchases/builds 3-4 of them, it may potentially consider placing one in each fleet, as command ships and for the prestige value. But again, not only has construction not started on these ships, but the deal has not even been finalized. Given the construction tempo of Russian shipyards (and assuming that at least some of the ships will be built in Russia), the third ship of this class is unlikely to be completed much before 2017.

But even if this shipbuilding program is carried out in full, this will still mean that the BSF ten years from now will be significantly less powerful and numerous than it is today, even though today’s fleet is already just a shadow of the Soviet Black Sea Fleet. The Gorshkov is a fine frigate, but it’s still a pretty small ship by comparison with the cruisers and destroyers that the fleet has had until now, not to mention the United States’ Arleigh Burke and Zumwalt destroyers.

Furthermore, the current deal has left unclear the question of whether new ships will be allowed to be based in Sevastopol. The 1997 treaty prohibited the basing of new ships there, so all new BSF ships have been based in Novorossiisk. The new agreement does not explicitly address this question, but does state that it is simply an extension of the 1997 treaty. This implies that the basing of new ships in Sevastopol will still be prohibited. I would imagine that either a side deal will be made in fairly short order to allow the basing of new ships or (less likely) such ships will simply be sent to Sevastopol without an explicit change in the rules. In either case, though, this will cause another round of political strife in Ukraine and provide the opposition with another opportunity to cast President Yanukovich as a traitor.

Overall, the military capabilities of the BSF will remain relatively low and will continue to decline over the next decade, though the agreement does allow for the possibility of a revitalization sometime down the road. I will address the strategic implications of this agreement for Black Sea security in my next post.

The following article recently appeared in the Russian Analytical Digest.[1] Some of the research for this article was carried out under the auspices of CNA Strategic Studies.

The Recent History of the Sevastopol Basing Issue

The current agreement on the status of the Russian Fleet’s Sevastopol Navy base was signed in May 1997. According to the agreement, the Soviet Black Sea Fleet (BSF) was initially divided evenly between Russia and Ukraine. Ukraine subsequently transferred most of its portion of the fleet back to Russia. In the end, Russia received 82 percent of the former Soviet Black Sea Fleet’s assets. The agreement recognized Ukraine’s sovereignty over Sevastopol and its harbor facilities, but allowed Russia to lease the bulk of the fleet’s Sevastopol facilities for 20 years for a payment of $97.75 million per year. Russia also retained criminal jurisdiction over its troops in the city.

The agreement expires in 2017, though there is a clause stating that it will be automatically renewed for a further five years unless one of the parties gives one year’s advance notice in writing that it wishes to terminate the accord in 2017. While the official position of the Ukrainian government has always been that the agreement would not be renewed, the political tension caused by the summer 2008 war in Georgia brought this issue to the fore. Ukrainian politicians stated that the Russian Navy should begin preparations for withdrawal from the base and provided the Russian government with a memorandum on the timing and steps necessary to withdraw the fleet in a timely manner. The official Russian position is that the Russian Navy would like to negotiate an extension of the lease, but is planning for the possibility that it will be forced to leave Sevastopol at the end of the agreement. The Russian government has stated that it will not consider withdrawal plans prior to the agreement’s expiration.

Recently, some nationalistically-minded politicians and retired admirals have made statements indicating that Russia has no intention of ever leaving the Sevastopol base. For example, former Black Sea Fleet commander Admiral Igor Kasatonov at one point stated that 2017 is a significant date only for “Russophobic” politicians. “The Black Sea Fleet is in Sevastopol forever… It will retain its base in Sevastopol, another will be built in Novorossiisk, Tuapse, maybe also in Sukhumi, if there is a need.” More recently, Mikhail Nenashev, a Russian State Duma deputy who serves on the Duma’s Committee on Defense and also heads the Russian movement to support the navy, argued that Moscow plans to continue to develop the Black Sea Fleet’s infrastructure, both in Russia and in the Crimea.

The Impact of Recent Political Developments

While President Yanukovich certainly has a more pragmatic attitude toward Russia than his predecessor, this does not necessarily mean that he will be eager to extend Russia’s lease on its naval base. It is after all a very controversial political issue in Ukraine and he may not want to take any actions that exacerbate existing regional and ideological divisions. One poll, conducted last fall, indicates that only 17 percent of Ukrainians support an extension, while 22 percent want the Russian navy out even before the agreement expires in 2017. For a president who is seen by a large part of the population as excessively pro-Russian and who was elected with less than fifty percent of the total vote, going against public opinion on this issue may prove tricky.

Second, there is the constitutional issue. The Ukrainian constitution prohibits the placement of foreign military bases on Ukrainian territory. The current Russian navy base is permitted because of a separate article that allows for the temporary placement of foreign bases as part of a transition period that was designed to smooth the process of Ukraine solidifying its independence in the mid-1990s. As one of his last acts, President Yushchenko asked the Ukrainian Constitutional Court to rule on the contradiction between these articles. Regardless of the impact of any future court ruling based on this request, there is widespread consensus in Ukraine that the renewal of the basing agreement would require a constitutional amendment, which would in turn require a two-thirds vote in the Ukrainian parliament.

Finally, there are economic issues. The initial signals given by Yanukovich in his first weeks in office indicate that he is willing to discuss the future status of Russia’s Black Sea Fleet, but only in the context of a wide-ranging negotiation that includes a whole set of issues. Without doubt, he will ask for a significant increase in the amount paid by Russia to lease the base – Russian sources believe that the absolute minimum that Ukraine would agree to is $1 billion per year (i.e. a tenfold increase), while the Ukrainian side may ask for as much as $5-10 billion per year. In addition, Yanukovich is likely to seek additional Russian investments in regional infrastructure. He may also tie other issues, such as an agreement on border delimitation and even favorable terms on natural gas transit and import pricing, to a positive outcome on the basing issue. On the other hand, the departure of the Russian fleet is likely to lead to significant economic dislocation in Sevastopol, where it is one of the largest employers. This may in turn lead to social protests and even anti-government political agitation among the mostly pro-Russian population. Thus, even if the basing agreement is eventually renewed, it will not be an easy process and is likely to result in significant tension with Russia.

Alternative Basing Options

Given the relatively poor relations between Russia and Ukraine during the Yushchenko presidency, it is not surprising that in the last few years Russian naval officials and military analysts began to discuss possible alternatives for basing the Black Sea Fleet. One obvious alternative is the existing naval base at Novorossiisk, which has been expanded over the last several years and currently hosts a variety of smaller ships, including the fleet’s two missile hovercraft, some small anti-submarine warfare ships, and the fleet’s newer minesweepers. The commander of the BSF argues that while it would be theoretically possible to expand this base to house all the BSF ships, the reality is that doing so would have a negative economic impact on the region by creating bottlenecks at Novorossiisk’s busy commercial port. The resulting delays could lead commercial shippers to increase their use of Ukrainian ports at Russia’s expense. Russian commanders also contend that the base is unsuitable because of climate conditions in the area. An additional base at Temriuk will only be useful for smaller ships and has the disadvantage of being located on the Azov Sea, making it easy in the event of hostilities for enemy navies to trap ships there by blockading the Kerch Strait.

Some analysts propose building an additional base near Novorossiisk, either to the northwest on the Taman peninsula or to the southeast at Tuapse or Gelendzhik. These would both be possible locations, though the expense of building a new naval base from scratch would be quite significant, especially if it becomes necessary to buy out tourist infrastructure along the coast. Another, even less likely, possibility is to establish a second base at a foreign location. Two such locations have been proposed: Ochamchira in Abkhazia and Tartus in Syria.

In the aftermath of the Georgia War, Sergei Bagapsh, the President of Abkhazia, offered to have Russian ships based at Ochamchira. While this offer was initially taken up as a serious possibility by the Russian media, subsequent discussions led Bagapsh to issue a clarification in which he said that Abkhazia will not become a permanent base for the Black Sea Fleet, though facilities could be developed to host BSF ships when necessary to counter potential Georgian attacks. In any case, the harbor at Ochamchira is too small to host more than a few Russian ships. For this reason, the basing agreement signed last month between Abkhaz President Bagapsh and Russian President Medvedev will provide the Russian Navy with the opportunity to temporarily base some ships in Abkhazia. At least two patrol craft belonging to the maritime border guard will be permanently based at Ochamchira, but there will not be a permanent Russian naval presence there for the foreseeable future. At the same time, it is possible that the Russian Navy will at least temporarily base its missile ships there after 2017 if forced to relocate from Sevastopol while an alternative base is prepared. This would free up pier space for the larger ships in Novorossisk.

Even before the Georgia War, the Russian government announced that it was cleaning and upgrading its existing base in Tartus, Syria. This base served as a refueling and repair station for the Soviet Navy’s Mediterranean squadron, but has been largely vacant since 1991. It has facilities to house several large ships. Speculation about the relocation of all or part of the Black Sea Fleet to Tartus in 2017 arose in conjunction with the Syrian President’s visit to Moscow in mid-August 2008. Bashar Assad’s strong support for Russian actions in the Georgia War and offer to further develop the Russian-Syrian military partnership led to speculation that a number of Black Sea Fleet ships could be relocated to Tartus. Efforts to expand Russia’s naval presence in Syria continue, as made clear in a recent semi-official review of Russian military policy toward the region, which indicated that the potential closure of the Sevastopol base was one of the factors that obligated Russia to further develop the base at Tartus.[2] However, the base currently only has three piers, which would be insufficient for more than a small part of the Black Sea Fleet. Any expansion would face large construction costs plus the likelihood of high fees for the lease of additional land. It is far more likely that Tartus will resume its role as a maintenance and supply base for the Russian Navy, especially given government promises to expand the Navy’s presence in the Mediterranean and perhaps even to reestablish the Mediterranean squadron.

Prospects for the Future

Russian leaders are not willing to openly discuss the likelihood of the fleet’s departure with considerable time remaining on the existing deal since they believe that in time they can reach agreement with Ukrainian leaders on a renewal. At the same time, for Yanukovich there is little political benefit, and potentially a high cost, to compromising. Given that seven years still remain on the lease, while President Yanukovich’s current term will end in five years, it seems likely that little progress on resolving the basing issue will be made before 2015.

By that time, the Black Sea Fleet’s situation could be very different. Most Russian navy specialists believe that the fleet will have few seaworthy ships left by then. The deputy mayor of Sevastopol recently noted that the Russian and Ukrainian Black Sea Fleets combined currently have less than 50 combat ships, compared to over 1,000 in Soviet times.[3] By 2017, most of the remaining ships will have exceeded the lifespan of their engines by a factor of three or four. As one Russian expert indicated, Russia does not currently have the capacity to rebuild the fleet by 2017 given the state of its shipbuilding industry. In this light, there may not be any need to build a new base in Novorossiisk or anywhere else, as the current facilities there will be more than sufficient to house the remaining seaworthy ships. Accordingly, the most important goal for the Russian Navy is to restore its domestic shipbuilding industry, a step that it is now starting to take by contemplating building French-designed ships under license in St. Petersburg.

For Ukraine, the most important goal is to design and enact a program for the economic development of the Crimea in general and Sevastopol in particular. The Russian Navy’s eventual departure will leave a giant hole in the region’s economy. Ukrainian politicians would be well served to be prepared to fill this hole before it leads to social unrest among the largely pro-Russian population of the region.

[2] The other factors included its potential to support anti-piracy operations in the Horn of Africa and the political need for an enhanced Russian naval presence in the Mediterranean.

[3] This seems an obvious exaggeration, as the total number of combat ships in the Soviet Navy at its peak in the mid-1980s was 2500, and the Black Sea Fleet was the third largest of four fleets. Nevertheless, the total number of combat ships has declined by approximately a factor of ten.

[1] The Russian Analytical Digest is a bi-weekly internet publication jointly produced by the Research Centre for East European Studies [Forschungsstelle Osteuropa] at the University of Bremen and the Center for Security Studies (CSS) at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology Zurich (ETH Zurich), and the Institute of History at the University of Basel. It is supported by the German Association for East European Studies (DGO). The Digest draws on contributions from the German-language Russland-Analysen, the CSS analytical network on Russia and Eurasia, and the Russian Regional Report.